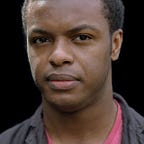

Good English: Where Are You From?

In July 2018 I booked an Uber to go see the Incredibles sequel. I am in Ottawa, Canada, a new country with different ways.

8 min readMay 3, 2019

My otherness grabs me like a warm hug from that aunt you don’t particularly like, but one your parents say you have to respect. The cabbie looks at my name again, and again and again — Tré Ventour. “Where are you from?” he throws at me. I saw this coming ten miles out, the question that’s been part of my life since I was old enough to speak. I translate this question as…