Notes from Conversations with My Mixed-Race Friends

The following derives from conversations I’ve had with mixed-race people with one Black or mixed-race (Black-racialised) parent and one white parent — on their experience of being mixed-race.

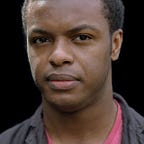

What can a Black man tell you about being mixed-race? What can I tell you about the vast number of different lives that envelope their experience? How one side of a family can hurl abuse at the other. What about the white father that others his Black son in-law? How about the taint of colourism that lurks in the crevices of multiracial Britain? The light versus dark arguments that impact all people of colour worldwide on every continent. Can I talk to you about relatives that hate their nieces, nephews and grandchildren with different coloured skin through a visceral lens? No, I write from a distance.The most I can relate, to those with multi-hued, many-faceted, complex identities are — the lines that have been drawn through Black Britishness, as Britishness has been whitewashed.

I can relate as far as British people of colour are made to feel marginalised in a country where indigenousness is white and immigrant is not. To be a person of colour in the UK is to be immigrant. It’s to be centre stage, forced into a monologue of performance and vanity. However, what I can talk about as an outsider, are the increasing number of interracial relationships — the number of white women having children with Black men, women that can often be ill-equipped in dealing with Black hair, as they say “how can you tame such a wild thing?” Crawling through a land that’s foreign to them, scrambling through Africa. Through thick roots, flicks, twists and twirls. Children with knots not seen in the Euro-centric straights of the white mother. My mixed friends talks to me how one of their parents has more privilege then they do and the challenges of that conversation. Let alone the white grandparents with grandchildren racialised as Black. I can somewhat understand the “unbelonging” my biracial colleagues have (to an extent) — being told that “they’re not Black enough” by Black people but then being told they act “too white” by their white friends.

Britain’s mixed population; do they feel more Black or white? No, they are people. And society often makes that choice for them. They are flesh and bone like everyone else. They are not exotic. They are personality and personhood.

Do the ones that come out white-passing — a blonde-haired blue-eyed boy with an Eritrean grandmother — acknowledge their privilege, despite half of them being African? The fact mixed-race can also can be darker than Lupita shows mixed-race does not have a face. And they don’t all have to like “Black music”. I can relate to the encounters when white people show their surprise when I express enjoyment for white British music — that I enjoy bands like The Clash but simultaneously will listen to Steel Pulse’s ‘Handsworth Revolution.’ The concept that biracial Britain, can enjoy music that sits outside of their “appeared minority” — it is possible that people who are mixed-race and racialised as Black by society can still enjoy the generic chart-toppers!

What about mixed-race role models? From Walter Tull to Akala to Rainbow Johnson (Black-ish) and Thandie Newton, our family and friends — what about the mixed-race history that isn’t taught in schools? What happens when people of Black and white parents grow up under only the white parent, not knowing about their African / Caribbean heritage? Not knowing how to maintain their skin? Not knowing the politics of Black African hair, and how it’s not okay for white people to plant their hands on your afro like it’s theirs.

Whilst there are arguments like “you’re creating more division if you keep talking about race” , those arguments only exist by societal design through the history of race and racism in this country. That goes back to the days of Black slave-servants in Georgian townhouses up and down the British isles, as well as in the big houses of the Caribbean and harvesting sugarcane crop on plantations — the children of slave and master in the house and in the field, but also in some cases, inheriting land from their father (master).

In the debates on race, why is the mixed-heritage narrative glossed over? In October, last year, at Black History Month I made an issue of (Black) mixed-race representation. I asked various local / regional community figures to come to talk to students about their racial identities. In asking, them I also made sure they knew they were not obligated, since I understand the semantics of tokenism and also the additional burden of emotional labour.

Mixed-heritage representation is more or less a whisper and we can do better. The television show Black-ish has done wonders with representation in not just the Black middle-class but also mixed-heritage identity / biracial families. But it is American. What about mixed-race Britain? The film and television industry is institutionally racist and they can do better in reflecting the diverse characters that inhabit our society, both in this country and the United States.