Where Are You From? (For ‘Effing Swings and Roundabouts’ by Lauren D’Alessandro-Heath)

I wrote this poem inspired by a poem by my friend Lauren, and an amusing video I keep seeing crop up on YouTube by the streaming platform BBC 3.

Part I

That day in history class, I was giving the teacher a grilling; talking at speed about the chosen truths they make kids read.

I paused, preparing my trident for war like Poseidon, preparing to debate with spitting snakes of Medusa.

Her speech hisses, her mouth a boneyard of teeth, like the streets of England below, a banjo with its heart ripped out

Her mouth leans in and asks:

“Where are you from?”

And I laugh, it’s not the first time I’ve been asked.

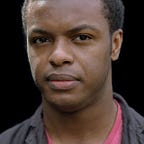

Could it be my brown skin, my frizzy hair? Alien? This Martian melanin man too dark to not have come from somewhere else.

My name has been Ventour and Griffiths. That’s where I am from. But I’m also Noel and Welsh. I come from Parkes and Baptiste. Moore and Clouden.

Slave names given to my ancestors who endured the Trade so I could have my life, that outlasted the raids of West Africa for gunpowder and gold.

I can trace these names back to Grenada and Jamaica. Ventour and Noel come from my mother’s family, originating in Grand Roy and St George’s.

Grenadian, or French like Mr Coloniser’s name.

My family back home, now country bumpkins, farmers, real estate holders, gardeners inheriting those allotments from those who carried our forbears as human cargo.

Grenada… Isle of Spice, paradise, soca and calypso, the world’s second biggest exporter of nutmeg, then there’s those submerged slave statues in St George’s Bay.

My father’s family…

Griffiths and Parkes, from Manchester and Portland, Jamaica. Jerk chicken and Rastafarianism. Reggae — Bob Marley, Gregory Isaacs,

sound systems boom from forests, parties in bush down far from GPS and Google Earth

— ackee and saltfish, dreadlocks and Patois.

Walking down a dirt road, there’ll be two men playing dominoes on a box next to a goat. Solve the riddle and they will tell you where you need to go like it’s a Skyrim side quest. I jest,

but I know both cultures and countries, that my names come from killing nations, the cremations of traditions, religions and languages.

Enslavement and dictatorships as blood sports from the ends of nine tails, and the flailing bodies from trees round Jamaica and Grenada;

Ghana and Nigeria; Côte d'Ivoire and Sénégal; from the ships that sailed slaves down the Thames, from the slave markets of Exeter, Bristol and Liverpool.

My names mean strong, mean survivor, like Nanny de Maroon.

Black women had it far worse than the men. Out there in the trenches, fighting rape and master. Fighting his wife, and the knife of the ship’s captain.

How many immigrants and refugees would have stayed in their homelands if the West hadn’t colonised these countries to begin with?

And I think it’s sad that more ten-year olds have heard of Henry VIII and Boudicca than of Cecil Rhodes, Rhodesia and blood diamonds.

I think it’s sad that more young Black men have heard of Versailles than of the Caribs or the Arawaks, than of boxing pioneers like Bill Richmond in the Georgian East End.

I think it’s sad that if schools teach on enslavement, they only talk about Wilberforce, Clarkson and Pitt, politicians who fought for abolition through politics, who never experienced master’s wrath, slave codes, whips or journeyed in the hulls of ships.

We don’t learn about the lawyers and the judges. We don’t learn about Lord Mansfield and the Zong or the case of Granvillle Sharpe and Jonathan Strong.

We don’t learn about the enslaved people who freed themselves, like Harriet Jacobs, like Nat Turner, like Harriet Tubman, like Nanny of the Maroons, like the island of Haiti.

We don’t learn about conquest through the courtroom; the United States versus the Amistad; Somerset versus Stewart; the real Solomon Northup versus Birch.

Part II

In 1765, a teenage boy was admitted to London’s St Bart’s. His master had beaten him badly. Left him to wind, rain and cold — left to die.

Sharpe found Jonathan, paid his medical bills and probably saved his life. Sharpe could have left him to the cold, sold him for gold.

But he didn’t…

An act of kindness. Two years later, Strong was abducted and sold to Jamaican enslaver. Determined to be free, he plead to Sharpe for help. Not wanting to become part of the next slave ship mutiny. Not wanting to be swallowed by the seas.

This case was not isolated. Blacks were being poached up and down this island nation, cartered onto ships and sold back into mass incarceration.

Sharpe was no lawyer, no legal training; he was just a man, a human being who saw an injustice being committed.

He was conscripted to the ideals of British freedom. This was about morality, this was about what made Strong’s life worth less than his own?

This was about how could he hold his head up in the street if he left this boy to certain death?

He had an unflinching moral compass. What was immoral could not be legal.

In 1772, he won a test case that outlawed slavery in England.

Where were Strong and Sharpe in my lessons?

Part III

I know we are descended from a mighty people, gave civilisation to the world, survived the hulls and holes of Jim Crow, Apartheid and Slavery.

People that innovated, created, loved — despite tortures unimaginable. They’re in my blood and in yours too. That’s how I became me and you became you.

This comes with good food, family barbeques, jokes and rice and kidney beans, a close-knit family, grandmothers whose first question when I walk through doors is:

You hungry? Have you eaten? Sustenance of life, soul food, dare I say poetry? My soul starting to shake, leaving my body as I find hidden wedges of Scotch Bonnet pepper thick like steak that Grandma has put in the fish cake.

Weekly, I am asked “Where are you from? Clearly not from here. But I speak the coloniser’s language pretty well. I do not speak the broken English-French Grenadian tongues that my Great-Grandma Toile did.

I investigate family mysteries, like having a white Irish great-great grandfather called Street. I see India in my grandmother, West Indian Indian…

many call it Cooli — many come from Trinidad where you’ll see a whole heap-ah South Asian-Indian-looking West Indians. More questions there!

All these questions tell me I have to validate my existence to see which country of poor Black people far far away I come from.

Stories that made me and my genealogy, scouting in pedigree and family history. I look at my reflection and see my face, a conglomerated peoples and cultures that drifted from place to place.

But when I am asked “Where are you from”, I laugh. I give them my history, that I speak bits and pieces of French, that I understand some of the split

tongues of the Caribbean, that I speak in metaphors and similes. That I speak in poetry and spoken word, villanelle, soliloquy and free verse.

I give them my life story, leaving them perplexed casting a hex on their ideas of indigenousness.

But I can laugh, when someone asks “Where are you from?” That my skin screams, Motherland. Not England, Africa.

And I watch my identities multiply into a million diaspora. Each once whole, whispering “We used to be whole. We used to be together.”